By ordering that Aadhaar be accepted as a legitimate form of identification for the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of the electoral rolls in Bihar, the Supreme Court on Monday significantly accelerated India’s ongoing electoral roll cleanup. However, the top court made it plain that Aadhaar was not a proof of citizenship and that the ECI had the right to confirm the authenticity of the documents.

Aadhaar will now be the 12th admissible document, joining the 11 others already recommended by the Election Commission of India (ECI), such as a passport, ration card, and birth certificate, but it will not serve as proof of citizenship, according to a bench of Justices Suryakant and Joymlaya Bagchi.

The Court firmly stated that Aadhaar is not proof of citizenship but merely confirmation of identification and place of habitation. As with other documents, the decision said, “Authorities would be entitled to verify the authenticity and genuineness of Aadhaar submitted.”

To guarantee adherence throughout the state, the ECI has been requested to post the order on its website and provide instructions throughout the day. The next hearing on the case is scheduled on September 15.

ECI opposes petitioners’ calls for inclusion.

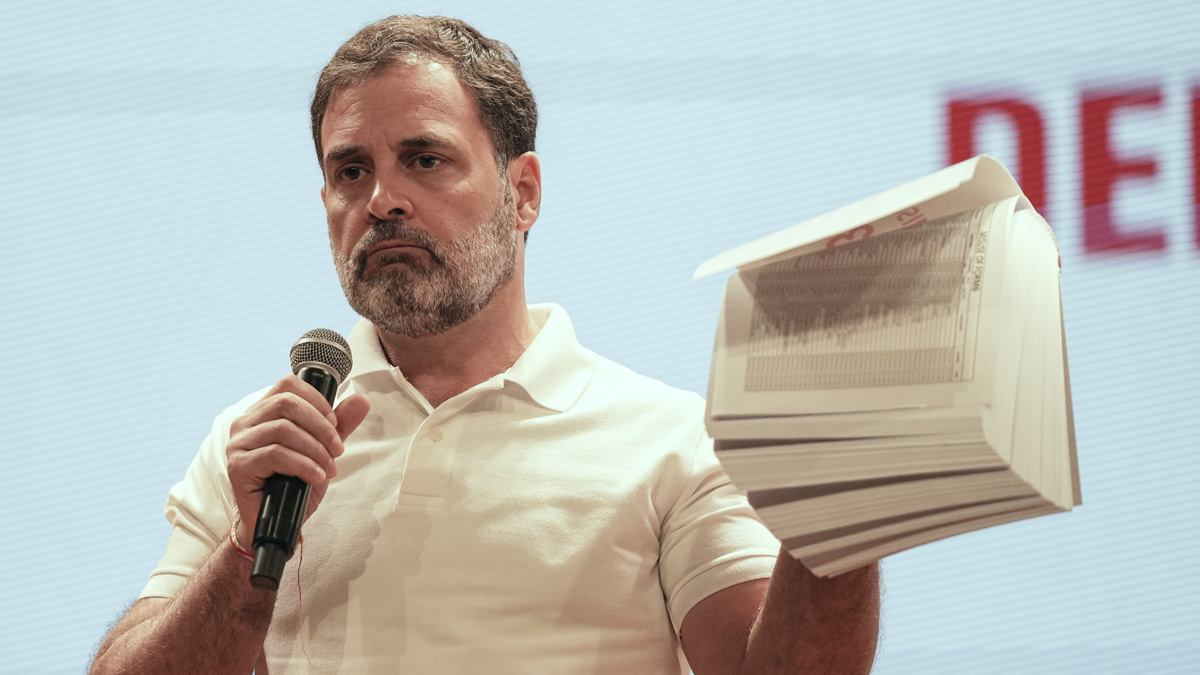

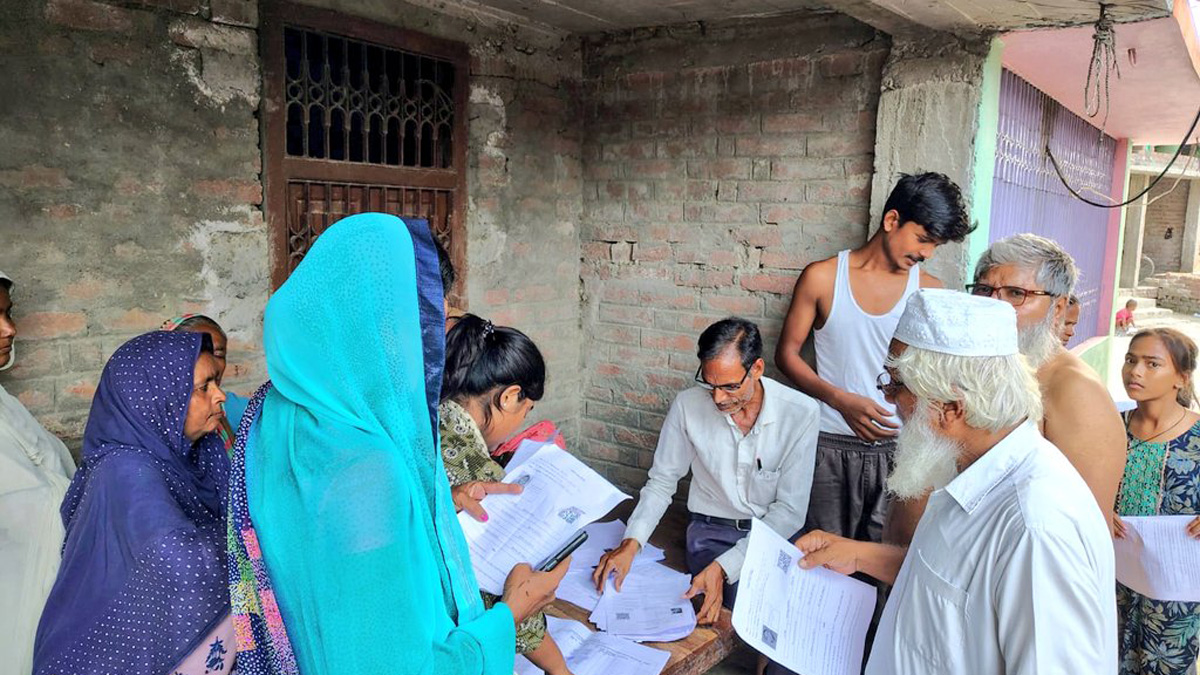

On behalf of the petitioners, senior attorneys Kapil Sibal, Gopal Sankaranarayanan, and Vrinda Grover urged the court to formally accept Aadhaar as the 12th document for voter roll verification. They contended that denying the poor access to Aadhaar would be equivalent to disenfranchisement because it is the only document they had. Sankaranarayanan stated that Aadhaar and the other 11 documents listed by the ECI are records of identity and residency rather than citizenship.

Sibal informed the court that although the Supreme Court had previously allowed the use of Aadhaar as a substitute, Booth Level Officers (BLOs) had been punished for accepting it. 24 affidavits from people in various districts who were unable to submit their Aadhaar have been collected. He pointed to what he called “ground-level resistance within the ECI’s machinery,” saying, “Disciplinary proceedings have already started against BLOs who accepted Aadhaar.”

Aadhaar is the only document that many impoverished residents own, thus Vrinda Grover added a social justice component by stating that eliminating it will unfairly affect the weaker members of society.

Senior counsel Rakesh Dwivedi, speaking on behalf of ECI, contended that Aadhaar lacks the legal standing of passports, which can also prove citizenship. Aadhaar, according to Dwivedi, is “not being considered as proof of citizenship” and may only serve as confirmation of residency. Additionally, the Commission asserted that no political party had yet to disclose any problems in the process and that 99 percent of applicants had already provided one of the 11 approved documents.

SC distinguishes between identity and citizenship.

The highest court made a careful distinction between citizenship and identity. “Many of the 11 documents are comprehensive proofs of citizenship,” noted Justice Joymalya Bagchi. Aadhaar, according to the petitioners, is not evidence of citizenship. Aadhaar is not legally recognised as proof of citizenship. Justice Bagchi added that Aadhaar can be used as proof of residency under Sections 23(4) and (5) of the Representation of the People Act.

Going one step further, Justice Kant stated verbally that although faked passports or Aadhaar documents might exist, it is ultimately the ECI’s duty to confirm their authenticity. The only document that the impoverished have is their Aadhaar. Grover had contended, “They want to remove the poor from the electoral roll,” to which the judge had replied, “The Commission has the duty of verification.”

The Court also examined whether its previous order to designate paralegal volunteers through the Bihar State Legal Services Authority to help individuals and political parties with the filing of claims and objections was being followed. Sankaranarayanan said that no volunteers had been assigned as of yet. Dwivedi retorted that the ECI was not responsible for this. The Bench instructed new compliance prior to the next hearing and warned authorities that the exercise must not become exclusionary.

It is important that Aadhaar’s authenticity be confirmed, just like any other document. It places the whole burden on the ECI’s verification system while tacitly acknowledging worries about forged Aadhaar cards. Although this could make things more difficult for ground authorities, it also makes sure that Aadhaar holders cannot be excluded outright.

The speed at which the ECI implements the Court’s mandate will probably be put to the test during the upcoming hearing on September 15. In the meantime, great attention will be paid to whether the Bihar example sets the tone for the entire nation during the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) process, which is due to start following the ECI’s meeting with state Chief Electoral Officers on September 10.

The legitimacy of an organisation that must protect against illegal immigrants while making sure that no eligible voter is excluded is also at risk, in addition to the integrity of the rolls.